Can cells from umbilical cords be used to treat patients with osteoarthritis?

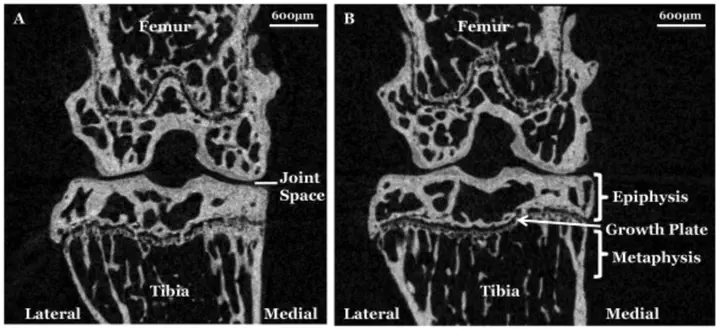

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a complex degenerative joint disease, characterised by degradation and loss of articular cartilage (causing the joint space to narrow), as well as a lot of changes in the bone, such as abnormal bony spurs or ‘osteophytes’ forming.

Currently, there are no effective pharmaceutical or non-surgical therapies to reverse osteoarthritis. Researchers around the world are seeking new approaches, including seeing if a biological approach such as cell therapy could be useful.

Here in Oswestry, we have been obtaining mesenchymal stromal or stem cells (MSCs) from human umbilical cords (UC-MSCs) for some years now. These are an attractive source of cells for regenerative medicine since they are fairly easy to obtain and grow and they also appear to have anti-inflammatory properties, which may be useful and make an immune reaction less likely if used in a different individual.

We are currently working with collaborators in other universities to see if the cells prepared here in Oswestry could delay osteoarthritis in their models.

Specifically, we are examining the effect of a single injection of UC-MSCs to determine if they can help repair or regenerate damaged joints.

If successful, it is likely they could be an excellent allogeneic (i.e. from another person) source of cells for the treatment of OA.

One of these (called the PMM or partial medial meniscectomy model) mimics end-stage osteoarthritis, with severe loss of cartilage and osteophyte formation appearing in the operated groups. Our results demonstrated that although the transplanted UC-MSCs did not recover joint damage induced by the PMM, as assessed histologically or by micro computed tomography (micro CT), the implanted cells did not appear to elicit an inflammatory response in the treated groups, even though they were from a different species (at least at the timepoints examined). Furthermore, there was marked variability between the UC donors, with a significantly reduced loss of joint space appearing at 12 weeks with one donor but not the other 2 donors’ cells. This suggests that some donors’ cells may have a greater therapeutic potential than others, highlighting the importance of characterising each batch of cells for allogeneic cell therapies.

The second model used a small isolated injury to the cartilage, which can lead to secondary osteoarthritis (and so significantly less severe than the aforementioned model). In this injury model we compared human UC-MSCs and bone marrow (BM)-derived MSCs, grown in a bioreactor (Quantum®), at repairing cartilage damage and preventing secondary OA. As in the other study, the groups treated with cells did not appear to show any macroscopic or microscopic signs of swelling/inflammation due to human cell implantation. Furthermore, when assessed histologically both human MSC treated groups had significantly better repair compared with the untreated group (ie without cells; Figure 7). Additionally, immunohistochemistry showed that there was more type II collagen in the repair tissue of those joints with better cartilage morphologically, as well as it containing many ‘tomato’-positive cells (which are derived from the joint interzone). These results suggest that up-scale manufactured UC-MSCs and BM-MSCs could be an effective therapy for treating cartilage injuries. The implanted MSCs did not appear to elicit an inflammatory response, further supporting their potential as an allogeneic treatment.